Prevention

Treatment

Recovery

Non COVID Related Protocols

Supporting Documents

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

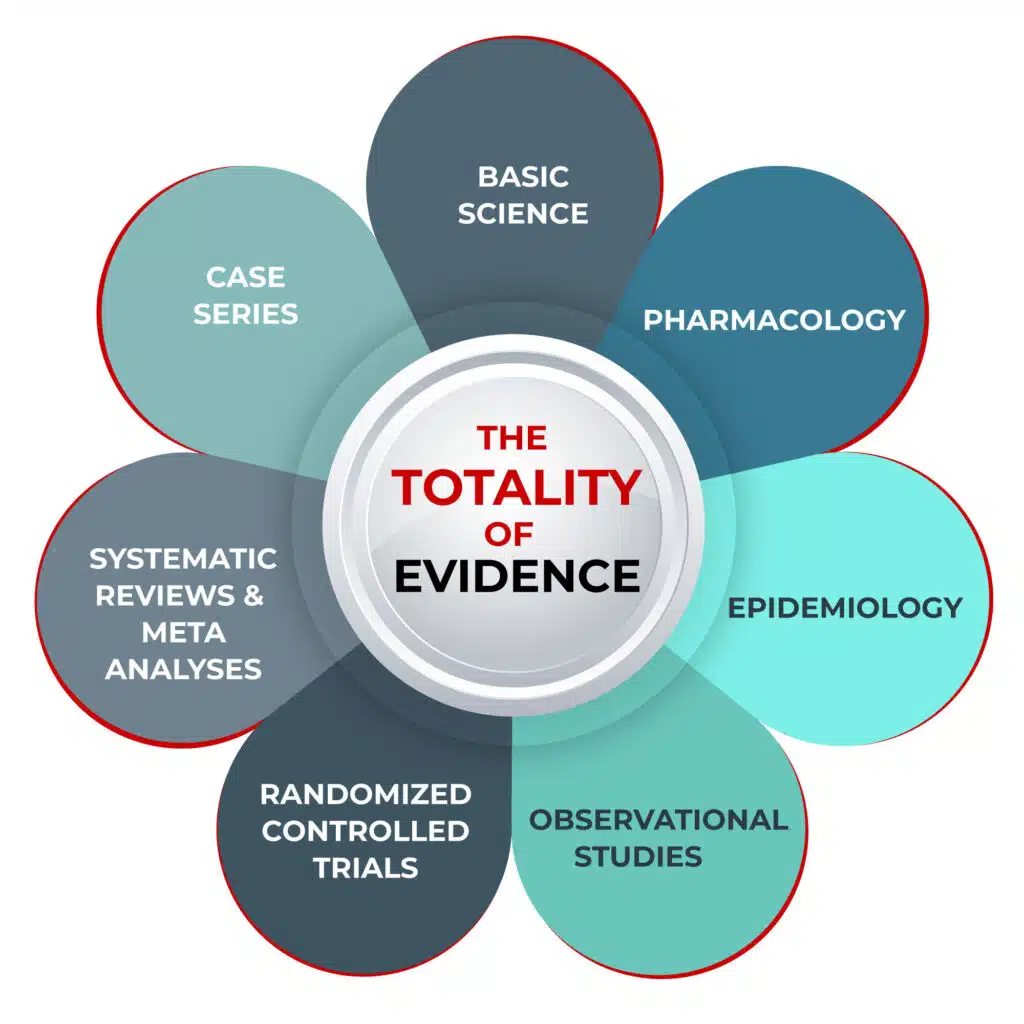

The Totality of Evidence

Decision making in medicine can be difficult. The best decisions are based on a combination of 1) the best available evidence; 2) the clinician’s experience, knowledge, and skills; and 3) the patient’s individual circumstances, wants, and needs.

Evidence can come in many forms: systematic reviews and meta-analyses (SRMAs), randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational controlled trials (OCTs), epidemiological analyses, case series, and patient anecdotes.

For a long time, RCTs were considered the ‘gold standard’ of evidence. In this type of clinical trial, participants are randomly assigned to either a treatment group or a control group. You may have heard the term RCT with reference to the various medications being considered as possible COVID-19 treatments.

Another term you may have heard is ‘meta-analysis’ or SRMA. SRMAs involve systematically reviewing the published literature to combine patient data (qualitative and quantitative) from numerous studies of a particular medical intervention to reach a conclusion that has greater statistical power than any single study. Because of the methodology of combining data from multiple studies, SRMAs look at an increased number of subjects, with greater diversity among subjects, and can identify accumulated effects.

However, both RCTs and SRMAs can suffer from the same flaws as other study designs and, unfortunately, these flaws are sometimes intentional due to the financial influences on both researchers and journal editors.

For example, SRMAs can lead to inaccurate results because of biased inclusion or exclusion of study data, flawed analyses, or the exclusion of unpublished studies.

The problems with RCTs are numerous, not least of which is the heavy influence of the pharmaceutical industry in the design and execution of studies, particularly in the larger, well-funded studies published in high-impact medical journals. Studies can be designed to produce a particular set of results, and often are. So much so that often RCTs do not accurately reflect real-world clinical impacts.

“It is simply no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published, or to rely on the judgment of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines,” wrote Dr. Marcia Angell, in her book The Truth About Drug Companies: How They Deceive Us and What to Do About It. “I take no pleasure in this conclusion, which I reached slowly and reluctantly over my two decades as an editor of the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM),” she continued.

Angell wrote that medical journals have become “primarily a marketing machine to sell drugs of dubious benefit,” and suggested that the pharmaceutical industry has so much wealth and power that it is able to co-opt any institution that might stand in its way. This, she says, includes Congress, the FDA, academic medical centers, “and the medical profession itself.”

Angell and her husband, Arthur Relman — a Harvard professor who also edited NEJM for decades — warned of the undue influence of the pharmaceutical industry for years, as did many other doctors, researchers and medical ethicists.

“The case against science is straightforward: much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue… In their quest for telling a compelling story, scientists too often sculpt data to fit their preferred theory of the world. Or they retrofit hypotheses to fit their data,” Richard Horton, Editor-in-Chief of The Lancet, wrote in 2015.

In 2005, Stanford professor John P. Ioannidis wrote an article entitled Why most published research findings are false, in which he states, “it is more likely for a research claim to be false than true. Moreover, for many current scientific fields, claimed research findings may often be simply accurate measures of the prevailing bias.”

In a 2014 paper, Ioannidis analyzed over 9,000 published meta-analyses in biomedicine and found that 1 in 5 were flawed beyond repair. Another 1 in 3 were redundant and unnecessary, while many others were decent but had “non-informative” evidence. Good and truly informative meta-analyses, he found, were a small minority (3%).

An analysis in 2011 looked at the overall quality of evidence behind 41 guidelines put out by the Infectious Diseases Society of America between 1994 and 2010. Only 14% of the guidelines were based on the supposed ‘gold standard’ of RCTs. Nearly 40% were based on expert opinion alone.

So where, you might ask, does that leave us when it comes to decision-making in healthcare?

A New Model: Weighing Up All the Evidence

Just as a jury is asked to review and evaluate all the evidence put forth during a trial, so too must clinicians look at all the best available evidence before them. We propose that researchers rely on the ‘totality of evidence’ and incorporate data from basic science, pharmacology, epidemiology, clinical experience, OCTs, RCTs, and SRMAs.

A common type of observational study is an OCT, where investigators retrospectively assess health outcomes among groups of participants according to a research plan or protocol. The outcomes of study subjects receiving medical interventions (such as drugs, devices, or procedures) are compared to the outcomes of subjects that did not. In these comparisons, the subjects are not randomly assigned to specific interventions by the investigator (as in a prospective RCT). Many discount the value of findings from OCTs due to an excessive concern that the results can be incorrectly interpreted due to the existence of unmeasured confounders, such as certain characteristics or the behavior of both the patients and the treating physicians.

Although such concerns are valid when relying on the results of a single OCT, the reality is that findings based on data from groups of OCTs are, on average, identical to the findings from groups of RCTs. Unfortunately, in modern medicine, this fact is rarely taught to or appreciated by physicians and researchers.

“The whole art of medicine is in observation,” said Dr. William Osler, a Canadian physician often described as the father of modern medicine.

A study published in 2014 looked at healthcare outcomes assessed with observational study designs compared with those assessed with randomized trials. The researchers reported that: “On average, there is little evidence for significant effect estimate differences between observational studies and RCTs, regardless of specific observational study design, heterogeneity, or inclusion of studies of pharmacological interventions.”

The American Thoracic Society (ATS), in an official 2020 research statement, said: “Observational studies can provide evidence in representative and diverse patient populations. Quality observational studies should be sought in the development of ATS clinical practice guidelines, and in medical decision making.”

The Totality of Evidence for Ivermectin in COVID-19

Based on the preceding, it is important to look at evidence from all sources when deciding whether to use a particular treatment approach. FLCCC used the totality of evidence approach when deciding on whether to recommend ivermectin as a potential treatment for COVID-19.

Some examples of the evidence we looked at include the following (not an exhaustive list):

- Basic science:

- The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro

- The broad spectrum antiviral ivermectin targets the host nuclear transport importin α/β1 heterodimer

- Ivermectin inhibits DNA polymerase UL42 of pseudorabies virus entrance into the nucleus and proliferation of the virus in vitro and vivo

- Ivermectin is a potent inhibitor of flavivirus replication specifically targeting NS3 helicase activity: new prospects for an old drug

- Nuclear localization of dengue virus (DENV) 1–4 non-structural protein 5; protection against all 4 DENV serotypes by the inhibitor Ivermectin

- Inhibition of Human Adenovirus Replication by the Importin α/β1 Nuclear Import Inhibitor Ivermectin

- Pharmacology:

- Ivermectin Docks to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor-binding Domain Attached to ACE2

- Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Deactivation via Spike Glycoprotein Shielding by Old Drugs, Bioinformatic Study

- Clinical Trial Conducted by MedinCell Confirms the Safety of Continuous Administration of Ivermectin

- Avermectin exerts anti-inflammatory effect by downregulating the nuclear transcription factor kappa-B and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation pathway

- Ivermectin inhibits LPS-induced production of inflammatory cytokines and improves LPS-induced survival in mice

- Effect of ivermectin on the cellular and humoral immune responses of rabbits

- Epidemiology:

- Uttar Pradesh government says early use of Ivermectin helped to keep positivity, deaths low

- Sharp Reductions in COVID-19 Case Fatalities and Excess Deaths in Peru in Close Time Conjunction, State-By-State, with Ivermectin Treatments

- Ivermectin: Partial monitoring results provided in extended use in positive patients (Argentina)

- Observational studies:

- Regular Use of Ivermectin as Prophylaxis for COVID-19 Led Up to a 92% Reduction in COVID-19 Mortality Rate in a Dose-Response Manner: Results of a Prospective Observational Study of a Strictly Controlled Population of 88,012 Subjects

- Use of Ivermectin Is Associated With Lower Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Ivermectin as Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for COVID-19 among Healthcare Providers in a Selected Tertiary Hospital in Dhaka – An Observational Study

- Why COVID-19 is not so spread in Africa: How does Ivermectin affect it?

- Randomized controlled trials:

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses:

- Review of the Emerging Evidence Demonstrating the Efficacy of Ivermectin in the Prophylaxis and Treatment of COVID-19 (this study was what is called a “narrative review.”)

- Ivermectin for Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis to Inform Clinical Guidelines

Further studies continue to look at the use of ivermectin in COVID-19. A full analysis of all studies is available at c19ivermectin.com, and a real-time meta-analysis is found at ivmmeta.com. You can also read the work of researchers such as Alexandros Marinos (Do Your Own Research) and Phil Harper (The Digger), or follow Dr. Pierre Kory’s writings about ivermectin and Big Pharma (Pierre Kory’s Medical Musings).

Video: